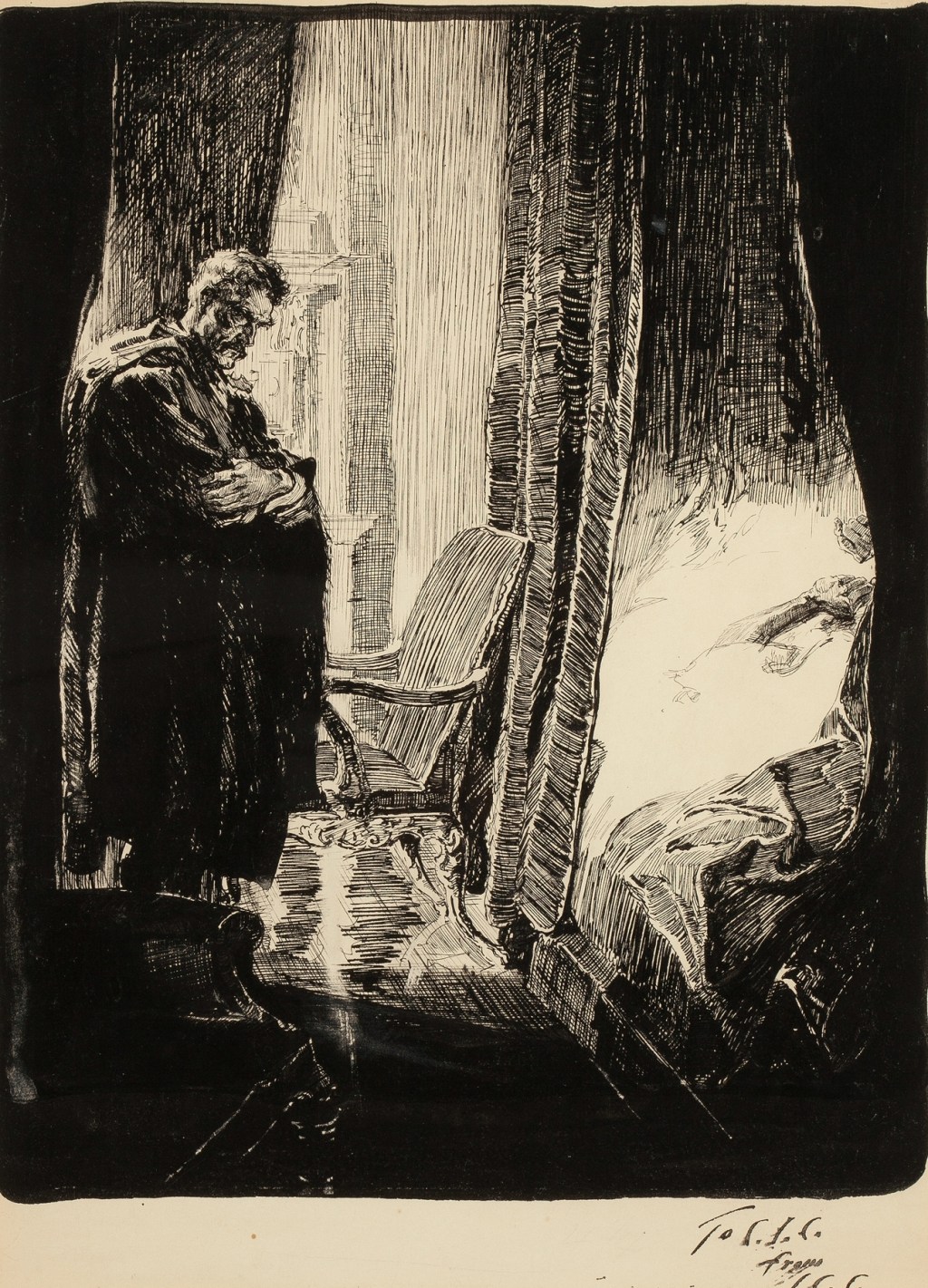

“Man In Bedroom” by Joseph Clement Coll, clearly contemplating how to paint like the masters of old.

No matter where you are in your art journey, there are always some works and draftsmen that leave you completely stumped, wondering if maybe your parents were right and you should get a grownup job. For me that might be someone like Jeff Watts, Joaquin Sorolla, or the inker behind the above illustration. It’s not so bad when it’s people with 30 years in the game, but when randoms you bump into on social media have more talent in their pinky than you have in your whole body, or a family friends 10 year old starts putting the moves on you, then it can be a little bit much. In a really funny way, this is the part of the journey that is both the most depressing and also potentially the most rewarding.

If you don’t decide to quit (which if you’re reading this you haven’t really quit) the next logical step many of us take is to sit down, shut up and start studying the masters… or at least that’s what we planned to do as we stare at a blank canvas feeling unworthy to even copy a singular stroke from the cracked outta their mind muthaf**ker in front of us.

Where the hell do you even start?

Even if you’ve somewhat successfully done a masters study in the past, there never quite comes a time when you feel qualified to emulate the thing in front of you. That special set of skills and years of experience that makes them a master is of course the very thing that is not so easily emulated. I’ve had this experience more times than I can count across many different fields in my pursuit of polymathism and I fortunately have found a few things that help A TON.

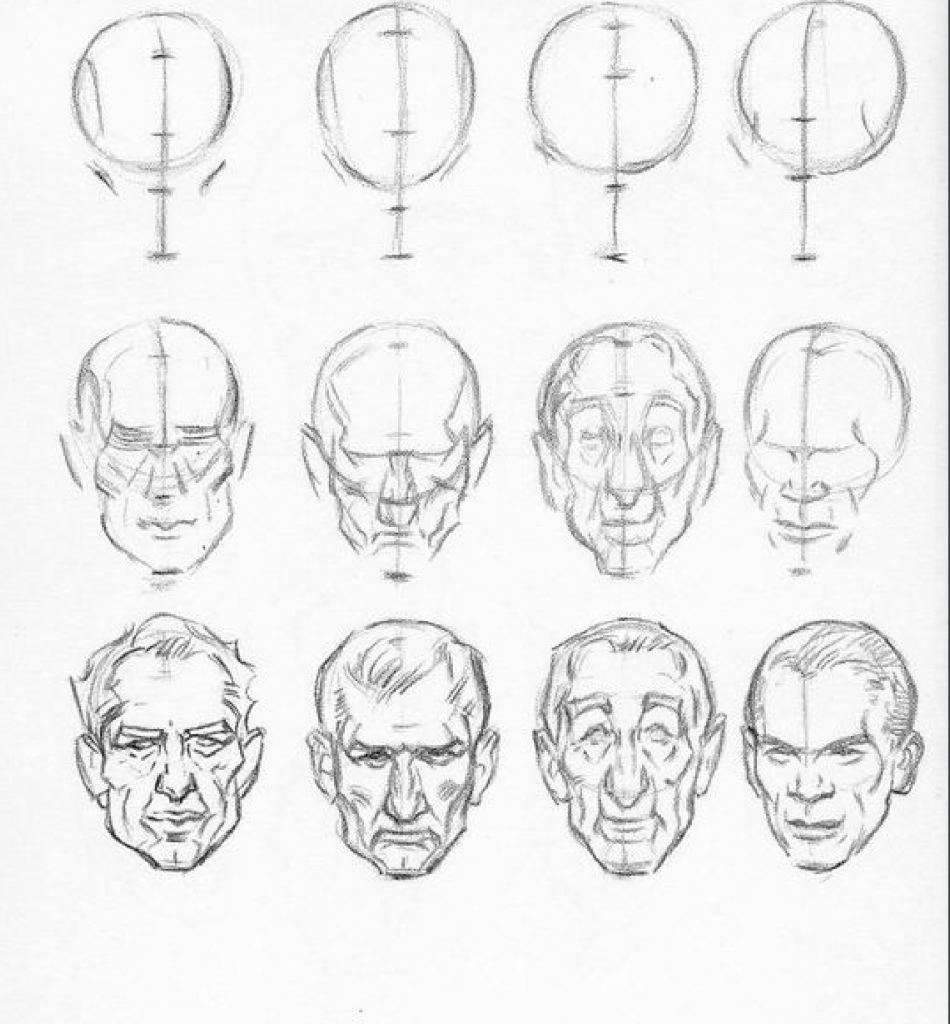

One of the most useful things I’ve found in learning from amazing artists, is don’t jump straight into the deep end. It can be very tempting to fool yourself into thinking that progress is made from trying to overcome really hard things and face your fears, and while somewhat true, if something is just hard and frustrating you’re probably not actually learning optimally. The thing about old paintings and masterworks is that many of the process steps and draftwork has been all but lost in the final piece, which can make it exceptionally difficult for anyone to deconstruct how on earth they did the thing. If you want to actually learn and make the study apart of your own process and art instead of just copying badly (it’s okay to admit your last drawing from Leyendecker may have been a little wanting) then we have to first deconstruct the master’s process.

The first thing that I like to do when studying an artist is find their sketches, particularly quick-sketches and any lay-in work they do before getting to the details and rendering. Why? Not only do I learn a lot about their decision making, how they measure, design shapes, poses, light and dark etc, I can also most of the time tease out the school of processes that they used to get good. If I can see that an artist uses frameworks from George Bridgman, or Frank Reilly, or something much older of course, then I can use any materials related to those things to further my training. You’d be surprised how many artists, even if their work is very stylized, use Bridgman or Reilly rhythms or Loomis ideas to start their drawings and think through problems. Another fantastic thing about something like quicksketch is there is really nothing to hide behind. You can tell how much dexterity someone has, their intuitive understanding of anatomy, or proportion, or weight and force distribution and perhaps most important, how they interpret and design based on the information they know. A simple framework I learned from Jeff Watts is art is part what you see, part what you know and part what you wish you saw. So while it’s imperative to know something about life, or something about light or perspective, you don’t become a phenomenal draftsmen who remains legendary for centuries by copying- you have to be an extraordinary designer, which is why we study from masters.

Something else I think a lot of newer artists in particular struggle with is trying to rush through or hack the training. I come from a very long background in lifehacking and biohacking and accelerated learning so I’m not saying wanting to optimize is the problem. The real problem I observe, is that so many people think the hacks or the apps and shortcuts will carry them to success even if they don’t try that hard. The cold hard truth is even if you pick the right things to practice and study from incredible mentors and the whole nine yards – if you’re not actually present and bringing your A game to your training, you will not get that much out of your practice. In fact, although it pains me to say it, just like that person at the gym who is swole but has horrible form, if you train your ass off even with a suboptimal protocol you’ll still probably improve much more than if you phone it in on a superior training regimen. Hacking, truthfully should be left to making sure you’re training the smartest way and doing the easy things, like getting good sleep, staying hydrated and programming breaks. You really don’t want to “hack” the actual effort. But really this is how you know if art is something you actually care about. Sometimes intense training will be, well, intense, but that doesn’t mean it should feel like a form of abuse. If you love what you get to do with art then you should feel fairly motivated to do the work.

The last thing that I have to say about training in art and trying to learn from the best is that in order to train like the best, you need to prepare like the best. Your work environment should be organized as if you are the Olympic equivalent of an artist. Your pencils should be immaculately sharpened and of a high quality, your paper shouldn’t make you wanna pull your hair out. If you’re penny pinching on your tools and equipment your are also pinching off your own success. That doesn’t mean you need expensive or buji stuff either, this is not about being pretentious, but if you’re trying to master digital art on a 20 dollar tablet that has 3 dead spots and the buttons don’t work, it’s time to treat yourself to something better. Use what you can afford, but recognize that getting good at anything is a matter of investment. A saying I love to remember is “what you appreciate, appreciates.”

Hope y’all found this helpful, I think I’ve basically said what I wanted about the topic at hand. If you find content like this useful punch in your email to stay updated, and if you really like it, please consider donating [here]. Anything and everything really helps and allows me to make better and better for you all. Cheers~

Leave a comment